Understanding pain that doesn’t come from injury

Many people experience ongoing aches, soreness, or “flu-like” body pain even when scans, labs, or exams look normal. This kind of pain is real, but it often reflects how the nervous system processes and amplifies signals rather than clear tissue damage (Clauw, 2015; Woolf, 2011).

One key player in this process is a brain chemical called norepinephrine.

What Is Norepinephrine?

Norepinephrine helps regulate:

- Alertness and energy

- Stress response

- Focus and motivation

- Pain control

It also plays a central role in the brain’s descending pain-modulation system—pathways that can turn down incoming pain signals before they become overwhelming (Millan, 2002; Pertovaara, 2006).

Norepinephrine as a Pain “Brake”

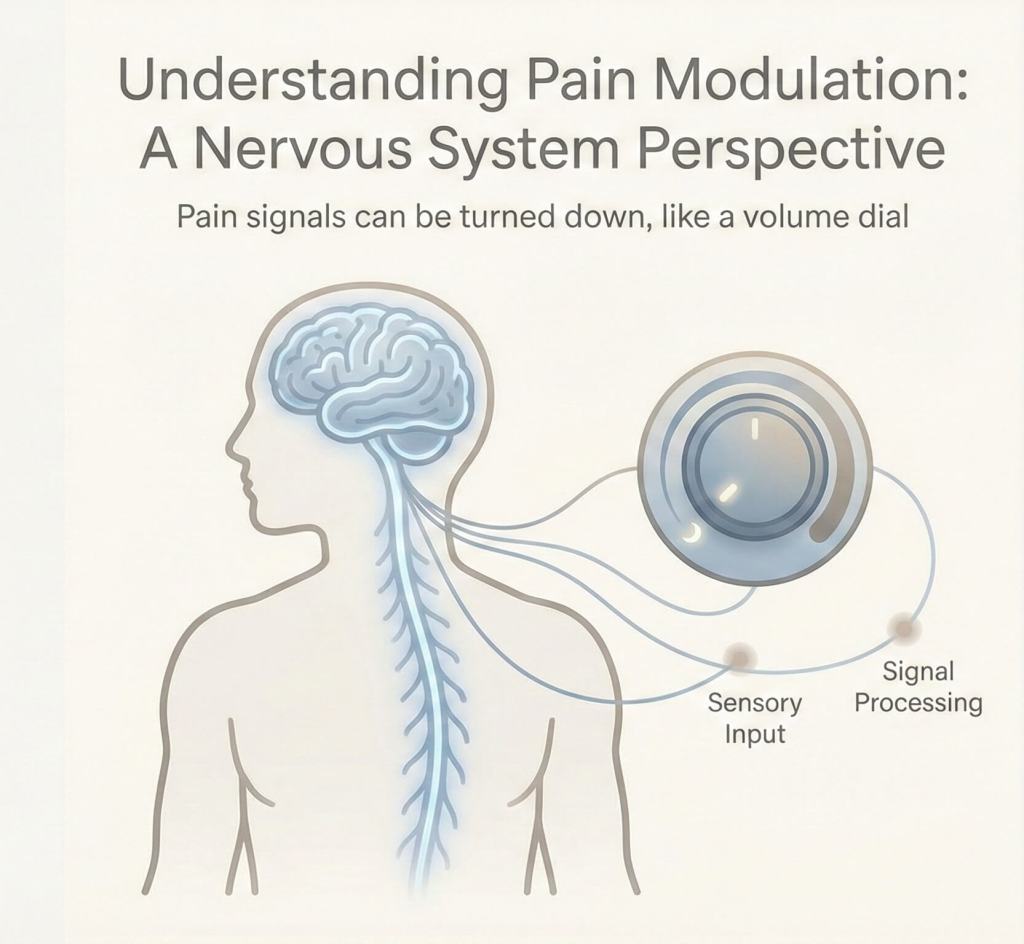

Pain signals travel upward from the body to the brain. At the same time, the brain sends signals downward through the spinal cord to regulate how intense those pain messages feel. Norepinephrine is one of the key neurotransmitters involved in this downward control system (Millan, 2002).

When norepinephrine signaling is functioning well, pain signals are filtered, minor discomfort stays minor, and the nervous system responds proportionally.

When norepinephrine is low or dysregulated, pain signals can become amplified. Normal sensations may feel achy or painful, and the nervous system can shift into an overprotective mode (Pertovaara, 2006; Woolf, 2011).

What This Kind of Pain Often Feels Like

People commonly describe:

- Diffuse muscle aches or stiffness

- Heaviness or soreness without a clear injury

- Pain that shifts locations

- Symptoms that worsen with stress or poor sleep

- Normal test results despite very real discomfort (Clauw, 2015)

In pain science, this pattern is often described as central sensitization, where the nervous system has effectively turned the “volume knob” up too high (Woolf, 2011).

Why This Happens

Low or unstable norepinephrine can weaken the brain’s ability to dampen pain signals, increase sensitivity in spinal cord and brain pathways, and allow stress and fatigue to magnify discomfort. Sleep disruption and chronic stress further interact with these systems, reinforcing pain sensitivity over time (Finan et al., 2013; Pertovaara, 2006).

This does not mean the pain is psychological or imagined. Rather, it reflects a nervous system that has shifted into a persistent state of high alert and sensory amplification (Woolf, 2011).

Why Some Medications Help Pain

Medications that increase norepinephrine signaling—such as SNRIs (e.g., duloxetine, venlafaxine) and some low-dose tricyclic antidepressants—are commonly used in chronic pain conditions, even when depressive symptoms are minimal or absent (Stahl, 2013).

This supports the idea that strengthening norepinephrine signaling can enhance the brain’s pain-control mechanisms, reducing the intensity of perceived pain rather than eliminating sensation altogether (Millan, 2002; Stahl, 2013).

Non-Medication Approaches That Can Help

Because norepinephrine is closely tied to stress, sleep, and energy regulation, several non-pharmacological strategies can reduce pain sensitivity over time:

- Consistent, restorative sleep (Finan et al., 2013)

- Gentle, paced movement that avoids overdo-and-crash cycles (Gatchel et al., 2007)

- Stress and threat reduction

- Pain-informed therapy approaches such as CBT or ACT (Gatchel et al., 2007)

- Education about pain amplification, which can help recalibrate the nervous system’s expectations (Woolf, 2011)

These approaches aim to calm the nervous system and restore regulation, rather than requiring people to push through pain.

Key Takeaway

If you experience ongoing body aches without clear injury:

- Your pain is real (Clauw, 2015).

- Your nervous system may be overprotecting you (Woolf, 2011).

- Norepinephrine plays a meaningful role in how strongly pain is felt (Millan, 2002; Pertovaara, 2006).

- There are multiple valid treatment pathways, both medical and non-medical (Finan et al., 2013; Gatchel et al., 2007).

Understanding what is happening is often a first step toward improving how your body feels.

References

Clauw, D. J. (2015). Diagnosing and treating chronic widespread pain. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 90(4), 528–546.

Finan, P. H., Goodin, B. R., & Smith, M. T. (2013). The association of sleep and pain: An update and a path forward. The Journal of Pain, 14(12), 1539–1552.

Gatchel, R. J., et al. (2007). The biopsychosocial approach to chronic pain. Psychological Bulletin, 133(4), 581–624.

Millan, M. J. (2002). Descending control of pain. Progress in Neurobiology, 66(6), 355–474.

Pertovaara, A. (2006). Noradrenergic pain modulation. Progress in Neurobiology, 80(2), 53–83.

Stahl, S. M. (2013). Mechanism of action of serotonin and noradrenaline reuptake inhibitors in the treatment of pain. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 74(9), e13.

Woolf, C. J. (2011). Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain, 152(3 Suppl), S2–S15.